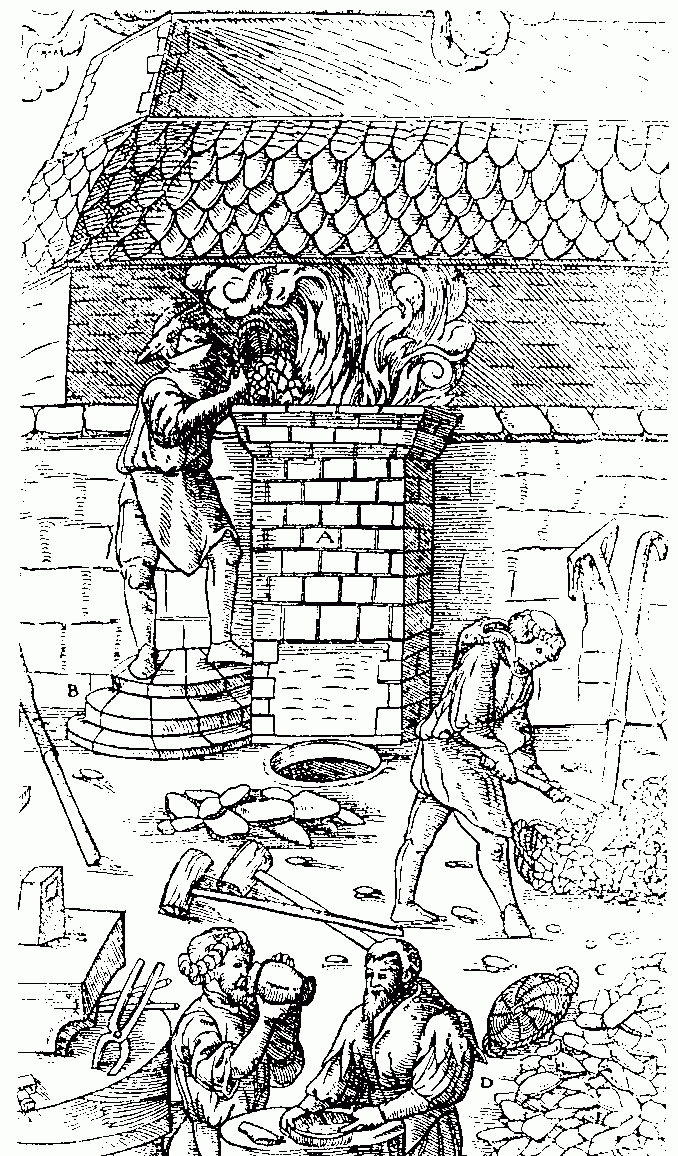

- Medieval bloomery smelting iron, woodcut from De Re Metallica by Georgius Agricola, 1556.

Benjamin Huntsman wanted to make better watch springs. He went to great lengths to do it, supposedly burying his failed experiments so no one else would find them. Enough of his story has passed into myth that I don’t know what to believe is true. That he was a watchmaker is not in doubt, and watch springs are a very demanding kind of steel.

One of the great myths is that there is a single best steel. Much like cars, steel alloys are designed for different purposes. Super hard steel breaks. Super resilient steel bends. The art is in the tuning, and in Huntsman’s time there were a lot of people tuning steel to many different purposes.

One ironmonger in Sheffield specialized in steel for surgical instruments and had a secret process to create his special brand. Another made steel specifically for scythes. There’s no reason to believe those specialty steels were poor quality, but their formulas are lost to time, buried under the tons of steel born in Huntsman’s crucibles, as lost as the Russian bulat, even if less celebrated.

Benjamin couldn’t convince the Sheffield industries to use his steel, so for years he sold it all to France. The French used it mostly to make cutlery, but there were a few innovations in clockwork.

The cutlery industry boomed alongside the cannonades and the governments. It became a steelclad world.

Catherine Louise and Jacques David II Lecoultre

Jacques David II Le Coultre was born to Abraham Joseph II in 1781. The Le Coultre family had lived in the Vallée de Joux since the tail end of the sixteenth century, but had only begun metalworking with Jacques’ grandfather, Abraham.

It was Jacques Le Coultre who started his family’s journey into watchmaking. As Sheffield has become known for its steel, Le Sentier is known for its watchmaking. Today it’s home to the Joux Valley Museum of Watchmaking.

The Le Coultre (or sometimes Lecoultre, and sometimes LeCoultre) family did not quickly get to watches. When Jacques brought his son Antoine into the family business, they were making primarily razors. This was the 1820’s. Antoine went to Geneva to study watchmaking and when he returned he and his father formed Jacques Lecoultre and Sons.

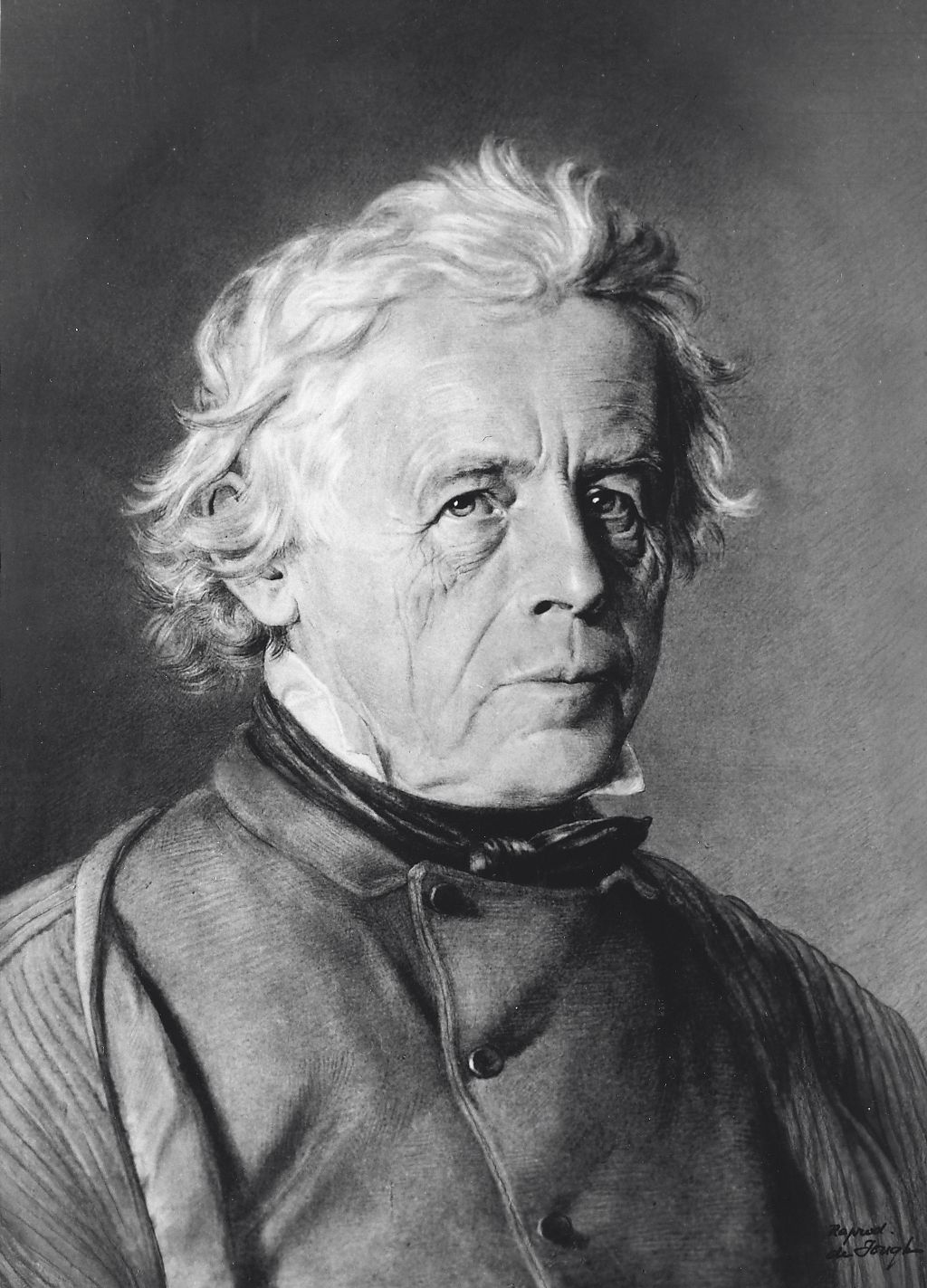

Antoine Lecoultre

Antoine Le Coultre opened his first workshop in Le Sentier, Switzerland in 1833. Over the decades he created many innovations including the first pinion-cutting machine (1826-1827), the first device to measure the micron (the Millionometer, in 1844), the swing winder (an early and important method for winding watches without a key, 1847), and others. His company exists today as Jaeger-LeCoultre, making very high end timepieces and instruments, including instrumentation panels for Citroën and Renault.

As interesting as Antoine’s career was, it was his father that is the focus of this piece, because it was his company that continued to produce razors. Some had a fixed frame with replaceable blades, others used the same blades but were permanently fixed into the frame.

An early advertisement for Le Coultre razors from the Augusta Chronicle, dated July 3rd, 1847

Contrary to some sources, Le Coultre did not invent the replaceable blade razor. The earliest of those were French from the initial explosion of razors made possible by Huntsman’s steel in the mid 1700’s.

To understand why this had an advantage, you need to understand a few things about straight razors.

Foremost being that they are designed to be honed by the user. The thickness of the spine and the width of the blade create the ideal angle for a sturdy, sharp cutting edge. There’s room for variation, but the razor is intended to lay flat on a stone for sharpening.

A very thin edge is easier to hone than a thicker one, but if there’s too much difference in thickness between the spine and the cutting edge, it becomes difficult to create a homogenous temper, meaning not all of the steel is equally hard. This can cause all kinds of havoc even on blades that don’t obviously break in the process. Thus was born the idea of a thin blade mounted in a thicker, separate spine.

Excerpt from a Wade & Butcher frameback ad. Boston, January 29th, 1827

Before Le Coultre, others had made thin blades that fit into a sturdier frame, including Ebenezer Rhodes and Wade & Butcher.

But Le Coultre’s razors were — and indeed are — superb razors. The fit and finish is indicative of their start as a producer of fine timepieces. They feel good in hand and take an exquisite edge.

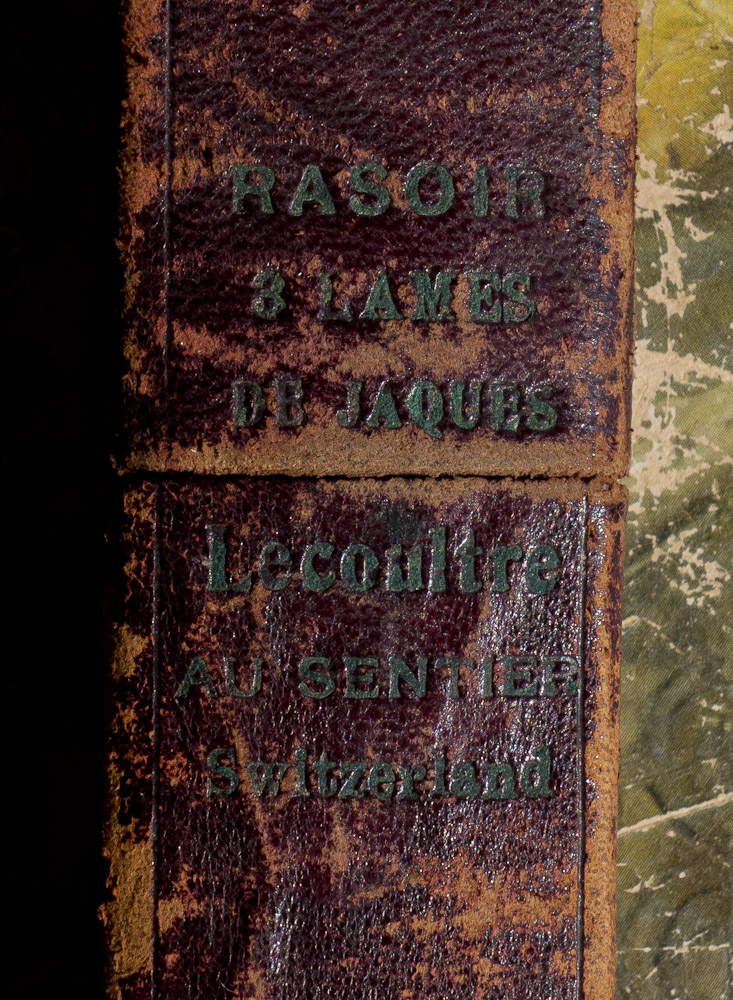

Razor and Three Blades

I purchased this razor from the excellent Guy Stuff in Carlsbad, California. These regularly go through eBay as well, but I hadn’t seen any in the fancy old celluloid scales. They’re not original to the blade, but they’re from the era and go nicely with the lines of the razor. Scales like these were made by specialist companies and sold to razor-manufacturers.

At the time, freelance grinders could be found in major cities who would take your old, rusted razor and regrind it to be functional again. Sometimes they would also replace broken scales, and likely could be paid to put a razor into something more fashionable.

The box, opened. D’aulnoy’s Fairy Tales used only for texture and color complement.

M M & Co.

The M M & Co stamp on the tang indicates it was sold through Mathey Brothers, Mathez & Co, the only importers for Le Coultre products in America in the late 1800’s through the early 1900’s.

The Mathey business started in 1883, moved through several different partnerships in quick succession and then settled on Mathey Brothers & Mathez. They continued operating from No. 16 Maiden Lane in New York City and sold a range of watches. Apparently also they sold razors, like this one. By 1901, they had expanded to take up 21 and 23 Maiden Lane.

The set I got came with three blades, each a different size. The box is designed to hold a tiny paper folio with sheets that separate the blades. It was likely made around the turn of the century, before Charles Colomb had taken over US sales.

Hidden folder

Each blade is stamped with a number, 1-3, there’s less difference between 1 and 2. The shorter blade changes the honing angle and produces a noticeably different shave. It has probably been ground down significantly.

Blades

The blades and the frame all need some cleaning, and there are chips to be honed out of the blades. Not too much trouble.

Celluloid Art Nouveau scales. Klimt’s love of naked women, Mucha’s vigilance for people sneaking around and a workaday execution create functional, flammable kitsch.

A razor that’s been eaten by decaying celluloid scales.

Scales like these were extremely popular around 1900 and there are many variations. They are made with celluloid. Originally a particular brand name for pyroxylin plastics, it’s come to be used for a wide range of products. Yes, it’s the same celluloid of exploding billiard balls and disintegrating (or exploding) film stock. The material is more stable depending on the fillers used. Transparent and translucent celluloids are the most likely to decompose, though even there not all colors are equally dangerous. Green and amber seem to be more stable than clear and yellow, but opaque yellow is quite stable — for a form of nitrocellulose. One of the breakdown byproducts of celluloid is nitric acid. If a razor is in a set of decomposing celluloid scales, the metal can be eaten away to nothing.

Many different patterns were made (and indeed a separate branch of razor collecting is dedicated to just the scales), often with some variation of half-naked woman cavorting with murdered plant life. Some were garishly painted, others more subtly tinted (like this one). The intent was to mimic ivory, in fact ‘ivorine’ was a trade name for a formulation of celluloid, also called ‘French Ivory’.

Most of these types of scales were probably made by a single company. That is to say, not the company who made the razor. While there were many different configurations of Le Coultre razors sold, including a set of 4 genuine ivory-scaled razors, each with a number etched on the back of the frame and packaged in a fancy leather box, most originally came in simple black horn scales.

1898 advertisement. To say that it’s doubtful that the blades last for ten years before they need honing is an understatement, but they are made from very good steel.

LeCoultre blade stamp. Le Sentier is also called Vallée de Joux. In the Lake Geneva district, it’s the center of Swiss watchmaking.

Finely milled set-screw.

Finally, the screw that holds the blade in place, at least on the later models, closely resembles the stem of a fine watch. It’s difficult to fully comprehend how precisely made it is without seeing it up close.

Even with the small nick in the end of the blade, I have gotten superb shaves from this razor.

Special thanks to Martin103 on the SRP and to Neil Miller who both found answers to questions that left me stumped. Without their help, an earlier draft of this essay would have been the final draft and it conflated Jacques Le Coultre and his son, Antoine.

I doubt father and son wanted to be that close.