William Greaves lead a remarkable life.

Born in 1752, little is known about his early years, or even how he started his business. There were a lot of men making things with steel and named William Greaves. There were, in general, a lot of men named William Greaves.

His childhood puts him firmly in the era when Sheffield cutlers were truly a cottage industry. This long quote from one F. Twiss, old-timer in 1876 talking about the heyday:

“Smithy, in Sheffield, is becoming an obsolete term; instead of speaking of ‘ahr smithy’, our cutlery makers have ‘my factory’ or ‘warehouse’ or ‘workshops.’ To realise the Old Sheffield smithy you must picture to yourself a stone building, of similar workmanship to common field walls, seven or eight yards long, by four wide and seven feet high, to the rise of the roof. It is open to the slates or thatch. The door is in the middle of one side, with the fireplace facing it; and at either end is a hearth with the bellows in the corner and the ‘stithy stocks’ 1Anvil stocks. in their proper situations. The walls are plastered over with clay or ‘wheel swarf’ 2A mixture of steel filings and stone grit turned to paste by the water running over the grindstone. to keep the wind out of the crevices; sometimes the luxury of a rough coat of lime may even be indulged in. The floor is of mud, the windows, about half a yard wide and a yard long, have white paper, well saturated in boiled oil, instead of glass, or in summer are open to the air. In one corner is a place partitioned off for ‘t’ mester’ as a warehouse or store room, and on each side are the work-boards with vices for hafters, putters together, etc. Over the fireplace is a paddywack almanack 3A cheap calendar, think they very early version of what appears in an auto-mechanic’s workshop. The etymology of the term is obscure but most likely is an ugly slur on the Irish., and the walls are covered with last dying speeches and confessions, ‘Death and the Lady’, wilful murders, Christmas carols, lists of all the running horses, and so forth. Hens use the smithy for their roosting place, and some times other live stock have a harbour there — as rabbits, guinea pigs, or ducks, while the walls are not destitute of singing birds cages. There are odorous out-offices close adjoining, and it is essential that the whole should be within easy call from the back door of ‘t’ mester’s’ house.

–Reminiscences of Old Sheffield: Its Streets and Its People edited by Robert Eadon Leader, 1876.

In his youth, William would have known Paradise Square first as pasture — Hicks’ stile-field 4Source Reminiscences of Old Sheffield: Its Streets and Its People, by R. E. Leader.. During his life it was transformed into a suburb and community center just north of the Cutler’s Hall. The major development was finished in 1771, the year after he’d begun a late apprenticeship with Joseph Worrall 5Apprentice lists of History of the Company of Cutlers of Hallmshire, Volume 2, by R. E. Leader this is slightly controversial, but all of the dates line up correctly.. Worrall was a cutler from what would become a south western suburb — Ranmoor, then part of Nether Green and Hanging Water.

In his youth, William would have known Paradise Square first as pasture — Hicks’ stile-field 4Source Reminiscences of Old Sheffield: Its Streets and Its People, by R. E. Leader.. During his life it was transformed into a suburb and community center just north of the Cutler’s Hall. The major development was finished in 1771, the year after he’d begun a late apprenticeship with Joseph Worrall 5Apprentice lists of History of the Company of Cutlers of Hallmshire, Volume 2, by R. E. Leader this is slightly controversial, but all of the dates line up correctly.. Worrall was a cutler from what would become a south western suburb — Ranmoor, then part of Nether Green and Hanging Water.

William completed his apprenticeship in 1776, but is listed in the Cutler’s Company books as co-apprenticing Samuel Lister with Worrall during that same year. His certificate of admission to the Company is dated September 27th, 1776. These certificates had a small lead piece attached with a ribbon, and the lead piece had his mark impressed on it, as well as in the margin of the document. The mark was also recorded in a master catalog of marks kept at the Cutler’s Hall.

In 1777 William married Ann Palfreyman. The next year their son Edward was born.

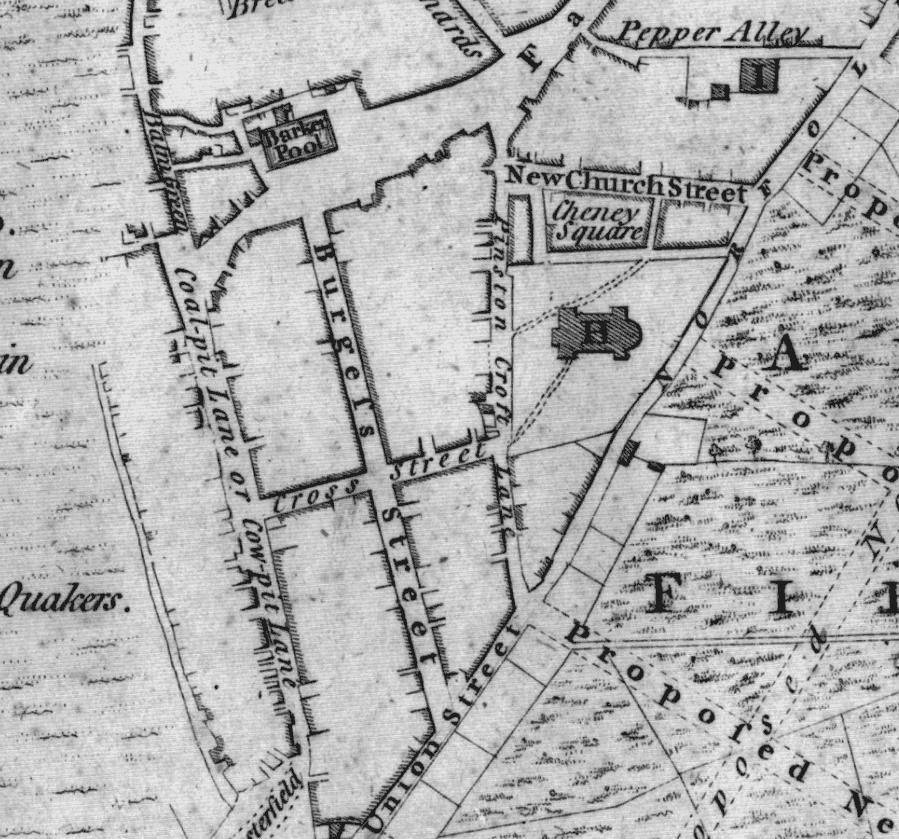

Leader’s Reminiscences has a recollection from Leighton that William Greaves launched his business in 1775 near the top of Burgess Street. Though he would move several times, the first move didn’t take him far, only to Cheney Square across from the ‘new’ church, Saint Paul’s Chapel.

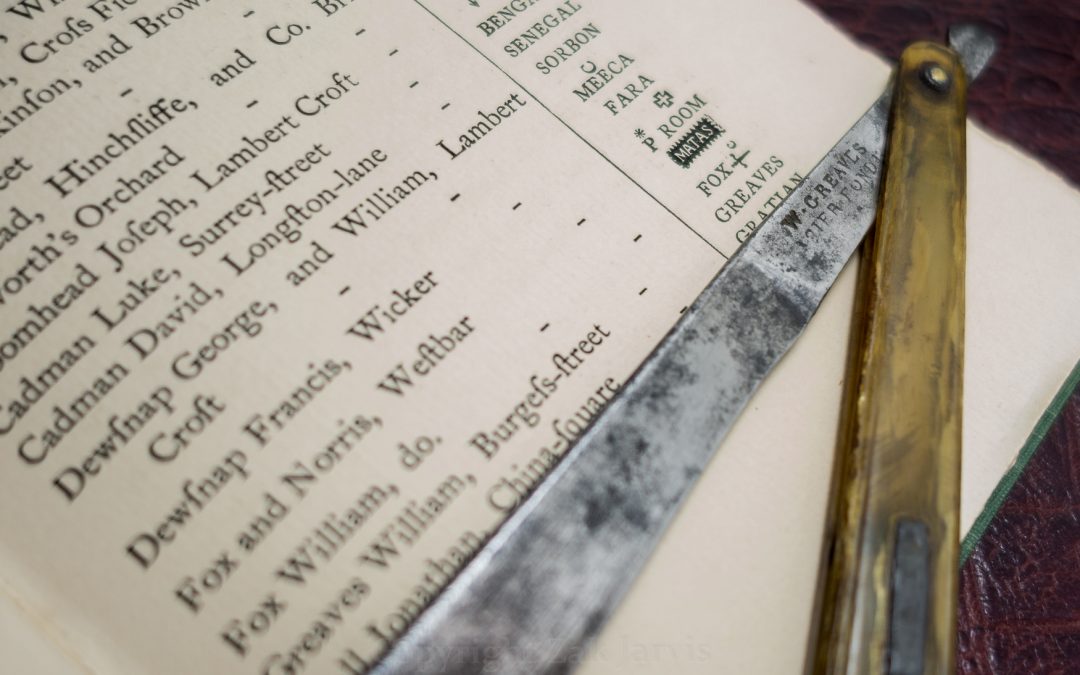

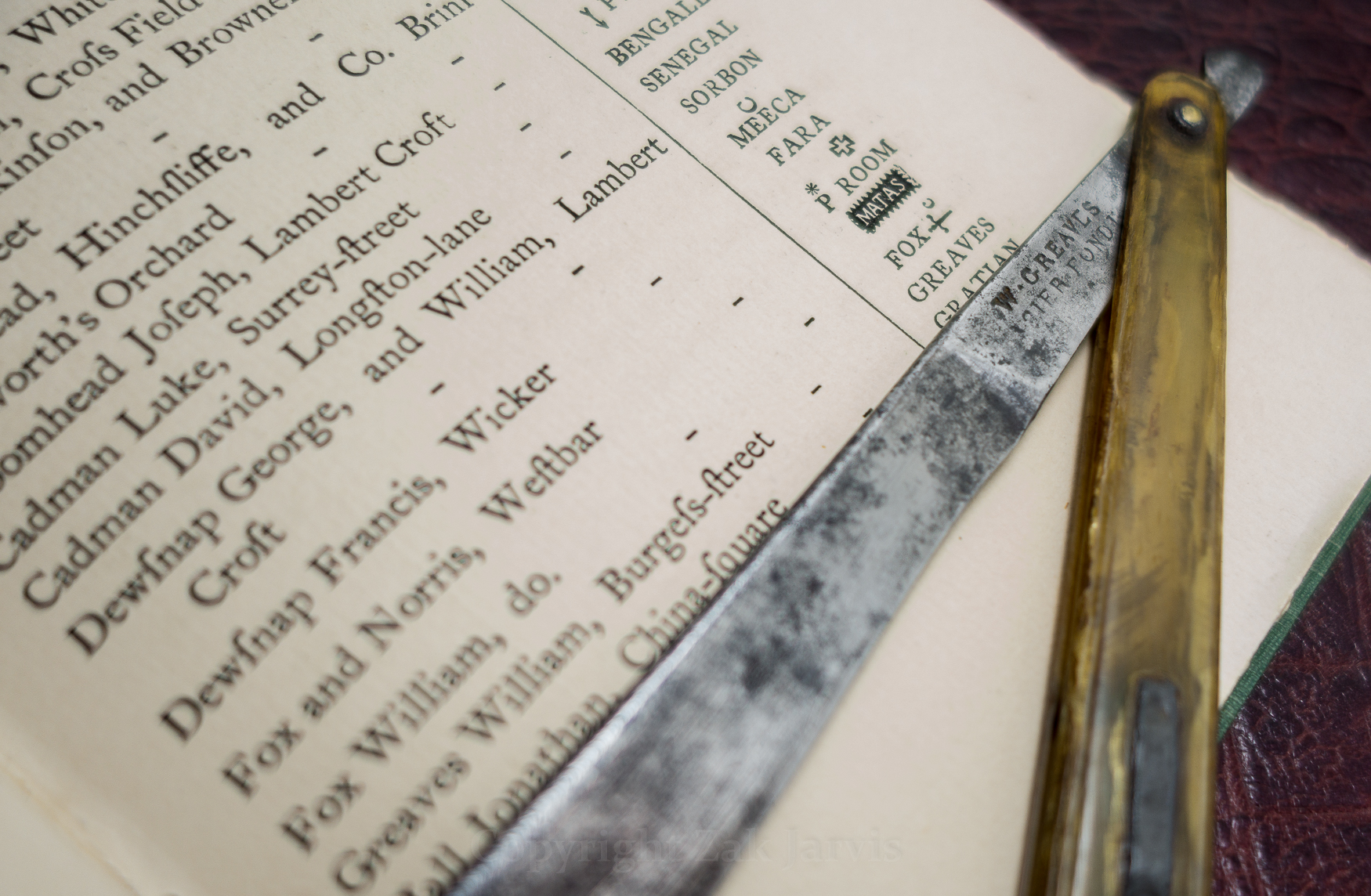

Gales & Martin published their Directory of Sheffield in 1787. On Page 23, under Razors made in Sheffield, there’s a listing for William Greaves on Burgess street. His mark then was simply GREAVES.

You might notice that the clipping from the map above, and the entry in Gales & Martin spell ‘Burgess’ oddly, with that character that looks like a lower-case f. That’s a long s, or ſ. Beginning around 1800, the long s was relegated to the same back-room of destitute alphabetical characters as thorn, yogh and eth. At least in English. By the end of its usage it was used anywhere a lower-case, non-terminal s would be used (hence Burgeſs street), though in earlier times it was sometimes used in other places an s might be used 6A nice write-up about the long s can be found here.. Indeed, you can see that the map and the directory use the letter differently.

Acier Fondu was a borrowing from the French cutlers of the time, who used that stamp to designate razors made from Huntsman’s cast steel process. Sheffield cutlers had eschewed Huntsman’s steel, but the French razors made with it proved popular enough that it was adopted back home as well.

During William Greaves life, the printed alphabet changed. That would be far from the only fundamental shift he would see though.

In 1789, a huge number of Sheffield cutlers submitted a petition to Parliament advocating for the abolition of slavery 7At one point, the BBC had an excellent article about this period. It has since been removed. Sheffield was a hotbed of political dissent and activism, see Ten Minutes Admonition, in Answer to Ten Minutes Caution.. They also petitioned that the Company of Cutlers be reigned in, complaining they’d become a club to oversee the interests of established cutlers at the expense of new freemen, and especially that their rules were unevenly applied.

The politics of the Company and of the cutlers within it went through incredible turmoil over the next thirty years.

According to one of Leader’s histories 8Reminiscences of Old Sheffield: Its Streets and Its People, By R.E. Leader. The histories of Leader exert an extraordinary gravity. He was the son of the publisher of The Sheffield Independent, and when he really got going the prose he wrote was so dull a diamond hone couldn’t whet it., by 1801 he’d moved a block to the East and set up shop as Wm. Greaves & Sons on Cheney Square. Richard and Edward were the sons. Edward he’d apprenticed himself, an apprenticeship completed in 1804. Richard was a businessman.

According to one of Leader’s histories 8Reminiscences of Old Sheffield: Its Streets and Its People, By R.E. Leader. The histories of Leader exert an extraordinary gravity. He was the son of the publisher of The Sheffield Independent, and when he really got going the prose he wrote was so dull a diamond hone couldn’t whet it., by 1801 he’d moved a block to the East and set up shop as Wm. Greaves & Sons on Cheney Square. Richard and Edward were the sons. Edward he’d apprenticed himself, an apprenticeship completed in 1804. Richard was a businessman.

Altogether, William and Ann had ten children, seven of whom survived to adulthood. Edward, Richard, Elizabeth, Mary Ann, Maria and two other daughters whose names I cannot find.

The early 1800’s saw the beginning of the American trade and it was this that provided the major engine for the Greaves company. The turn of the century metaphorically tilled a lot of fields. For ten years or so that business boomed, then it was cannons that did the booming.

Everyone’s business was a bit constrained in the years leading up to the War of 1812. Trade with America was problematic, but by the time the ink had dried on the treaty of Ghent merchant ships were laden with goods and sailing across the wide Atlantic.

For a few years, William and his sons operated from Hollis Croft at a building that Joseph Elliot would later occupy. In 1817 they moved to Division street. It was there that Richard and Edward began planning something extraordinary.

For a few years, William and his sons operated from Hollis Croft at a building that Joseph Elliot would later occupy. In 1817 they moved to Division street. It was there that Richard and Edward began planning something extraordinary.

The Sheffield Improvement Act of 1818 9You can read more about the act on Wikipedia brought gas lighting to the streets and a mandate to reduce the smoke from steam engines.

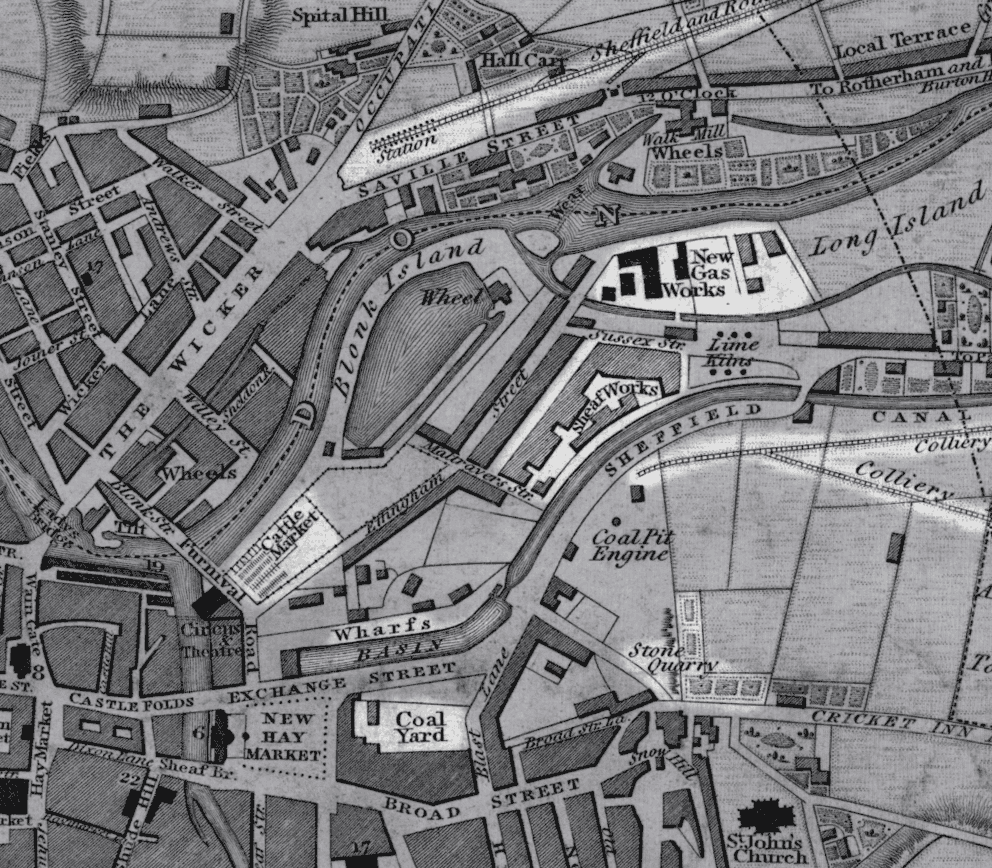

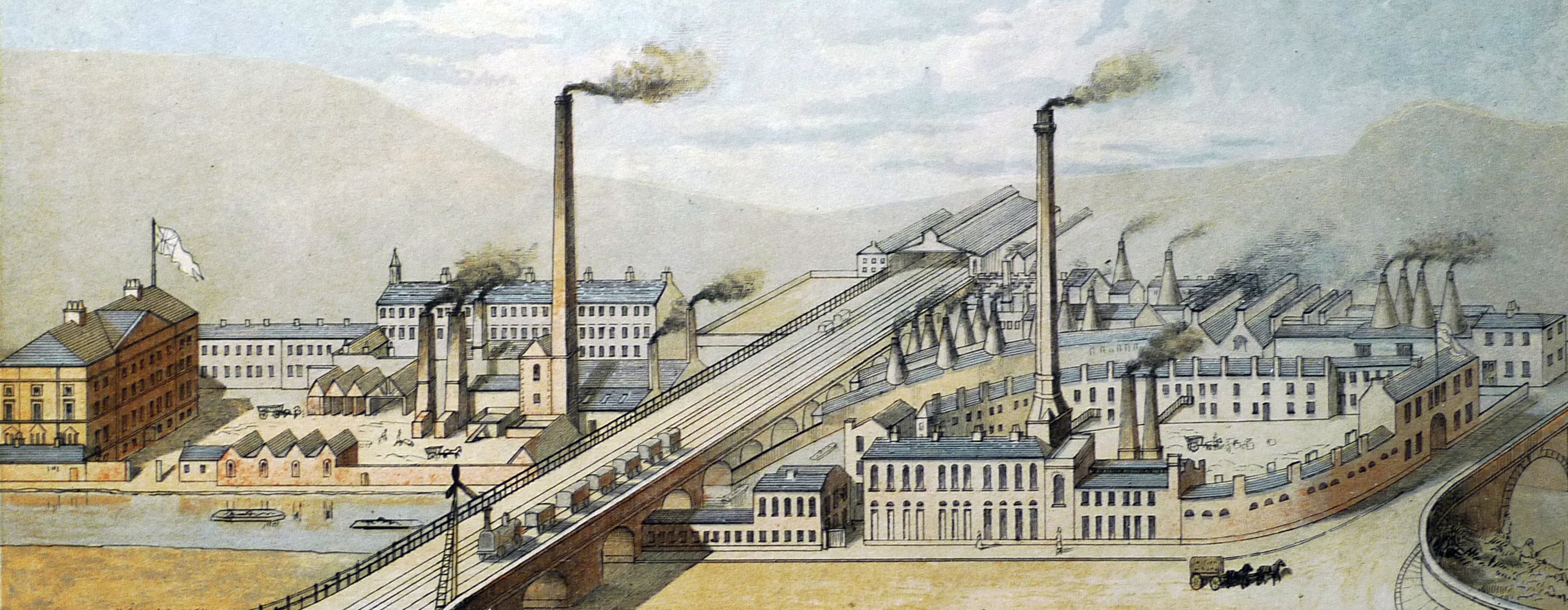

1819 saw the completion of the canal on the River Don, and with that William’s sons had what they needed to change Sheffield. It would take them some years to complete, but they were preparing a factory the likes of which Sheffield had ever seen.

From Division Street, which had been a small move for the company, they moved into the Sheaf Works, to the north east.

The Sheaf Works was centrally located to the gas works, for lighting, the coal yard for powering the steam engines, the River Don and the River Sheaf, the railyard, the cattle market (for horn), and a stone quarry. The factory was a monument to efficiency engineering, reputed to be largely the design of Richard Greaves. It opened in 1823 and cost a fortune: £50,000. Needless to say, business had been good to this point.

The story goes that ore came in one end of the factory and shipments of boxed, finished goods went out the other, directly onto barges for delivery. At the time, this was unheard of. The rest of Sheffield was producing cutlery with pieces from specialized vendors all over town — from hafters to refiners — no one was controlling every aspect of the production the way Greaves did.

Most of the goods went to America.

Business got better. By the time of his death, May 13th 1830, William Greaves was among the wealthiest men in Sheffield. He left his five daughters £30,000 each. He also left them apprentices from his factory. Mary Anne married John Bower Brown and Elizabeth married Thomas Blake. The company remained firmly in the hands of family, and they continued to do gangbuster business with America.

Richard Greaves — nicknamed Lord Sheffield, though not to be confused with the actual Lord Sheffield — never married. His sister Mary Anne kept house for him at Shire House where he lived out the last of his days. His agricultural holdings and property leases he left to Mary Anne, all the business dealings he left to his brother Edward, and in the event of Edward dying before him, to his partners John Fawcet and John Bower Brown. Richard died on the 25 of April, 1835. He was 55 years old. 10From “A South Yorkshire Family of Type Founders” by William Greaves Blake.

Edward lived at Woodside, near his sister Elizabeth and brother-in-law Thomas. He kept the business going along for another 11 years, but his health deteriorated horrifically. By the time of his death on October 6th, 1846, Edward could only sign his name as an X. He was restricted to a wheelchair, and his death certificate states the cause of his death as exhaustion from pressure sores. 11Same as above.

Edward left all his business holdings and property pertaining to the Sheaf Works to his nephews, Richard Edward Bower Brown (son of Mary Anne) and William Greaves Blake (son of Elizabeth), clearly hoping they would continue the business. Unfortunately, when Edward died both his nephews were too young to take over 12ditto. The company was dissolved in 1850, being parceled out to Thomas Turton and B.J. Eyre, each using different parts of the factory and producing different kinds of goods with the Greaves name on them.

Image courtesy of Geoffrey Tweedale

Sometime later in the 19th century, Frederick Mappin bought the property. It remained with his company until 1980, when it went derelict 13“Tweedale’s Directory of Sheffield Cutlery Manufacturers“, Geoffrey Tweedale.. Recent attempts at gentrification of the property have failed. All that remains is a single building which now serves as office space called Sheaf Quay.

So when I say that William Greaves lead a remarkable life, I am saying: he saw the printed alphabet change, he saw the town of his birth turn into a city, he saw the Company of Cutlers move from peak to trough and on the way back up, he saw his sons change what manufacturing meant in a city of factories. In the beginning, his job was done in shanty huts, by his death it was three-story factories.

Today the tomb of William Greaves sits behind a park bench at the Unitarian Chapel in Sheffield, just around the corner from the Sheffield Library.

Image courtesy of Geoffrey Tweedale

An earlier version of this appeared as a featured article on the Straight Razor Place.

Useful facts

Apprentice records

- William Greaves, son of Robert Greaves, cutler-grinder of Stannington, apprenticed to Joseph Worrall, Cutler of Ranmoor; 5 1/2 years, 1770. Freed 1776

- Edward Greaves, son of William, razorsmith: apprenticed to his father, Freed 1804

- Samuel Lister, son of William, apprenticed to William Greaves, Worrall, cutler Freed 1766

- James Kirkwood, son of Jason of Chesterfield, husbandman (farmer); to William Greaves, cutler, 7 years, 1784

- John Bellamy, son of John, apprenticed to William Greaves Razormaker, 1801

Marriages

- William Greaves to Ann Palfreyman,

May 19th, 1777 in Bradford at St. Peter’s - Thomas Blake to Elizabeth Greaves

May 20th, 1816 - John Bower Brown to Mary Anne Greaves

July 9th, 1836

Births & Deaths

- William Greaves

Born, 1752 in Stannington

Died May 13th, 1830 in Sheffield - Ann Palfreyman

Born 1752

Died February 18th, 1824 - Edward Greaves

Born 1778

Died October 6th, 1846 - Richard Greaves

Born 1780

Baptism June 30th, 1782 in Kirk Deighton, All Saints, Yorkshire

Died April 26th, 1835 - Maria Greaves

Born 1789

Died 1862 - Elizabeth Greaves

Born 1792 in Sheffield

Died May 11th, 1863 - Mary Anne Greaves

Born 1796

Died June 26th, 1873

- 1Anvil stocks.

- 2A mixture of steel filings and stone grit turned to paste by the water running over the grindstone.

- 3A cheap calendar, think they very early version of what appears in an auto-mechanic’s workshop. The etymology of the term is obscure but most likely is an ugly slur on the Irish.

- 4Source Reminiscences of Old Sheffield: Its Streets and Its People, by R. E. Leader.

- 5Apprentice lists of History of the Company of Cutlers of Hallmshire, Volume 2, by R. E. Leader this is slightly controversial, but all of the dates line up correctly.

- 6A nice write-up about the long s can be found here.

- 7At one point, the BBC had an excellent article about this period. It has since been removed. Sheffield was a hotbed of political dissent and activism, see Ten Minutes Admonition, in Answer to Ten Minutes Caution.

- 8Reminiscences of Old Sheffield: Its Streets and Its People, By R.E. Leader. The histories of Leader exert an extraordinary gravity. He was the son of the publisher of The Sheffield Independent, and when he really got going the prose he wrote was so dull a diamond hone couldn’t whet it.

- 9You can read more about the act on Wikipedia

- 10From “A South Yorkshire Family of Type Founders” by William Greaves Blake.

- 11Same as above.

- 12ditto

- 13“Tweedale’s Directory of Sheffield Cutlery Manufacturers“, Geoffrey Tweedale.